Or listen in your favorite podcast app

Apple Podcasts / Google Podcasts / Spotify

—

The Story is brought to you exclusively by Salesforce, a company that is committed to building a path toward Equality For All.

—

The man watched the boy from across the farm. The boy had arrived at dawn and was already covered in mud. He was too small to carry the large buckets of water from the well to the pig trough. Instead, he carried the smaller buckets and moved across the field without spilling a drop.

“He’s not afraid of work,” said a voice from the farmhouse.

The Reverend pointed to the young boy as he walked carrying the buckets.

“He’s a curious lad. You’ll like him.”

The Reverend and the man watched as the young boy made countless trips across the field in the warm Tennessee sun. The Reverend caught the boy’s eye and waved him over to where he and the man were standing.

“Jasper, this is Uncle Nearest. He’s the best whiskey maker I know of.”

Jasper nodded and smiled. Nearest liked him already.

Nearest was born into slavery in Maryland and sold to slave owners in Tennessee. He had many talents, one of which made him extremely valuable. Nearest was a slave who knew how to make whiskey. When he arrived in Tennessee, it wasn’t long before a Lutheran minister heard about his talents and sought him out.

The Reverend owned a small whiskey distillery in the back of his farmhouse, next to a winding creek. It was too expensive to own a slave who was a distiller, so The Reverend rented Nearest from his owners. The Reverend was a busy man, and he liked Uncle Nearest and often left him alone to tinker with his whiskey recipe.

Nearest was a tall man with broad shoulders. His hands were calloused from carrying whiskey barrels and moving water from the spring behind the farmhouse up to the distillery. He was a sharp dresser who walked with his head held high and spoke with competence.

Nearest took his craft seriously. He spent long hours each day developing and perfecting new methods of distilling. Soon The Reverend introduced him to young Jasper. Every day, Jasper would pepper Nearest with questions about making whiskey.

Finally, when Jasper turned 14, The Reverend sat him down and made the boy an offer.

“You are old enough to work with Nearest if you want,” said The Reverend. “He’s the best whiskey maker that I know.”

Jasper said yes, and showed up for his first day of work beaming with pride.

Nearest looked at Jasper.

“Run down to the spring and get fresh water and we’ll get to work.”

Jasper ran out the door grinning. Long days and nights of distilling followed. When The Reverend caught up with Nearest to see how the boy’s apprenticeship was going, The Reverend made one thing clear. He said, “I want him to become the world’s best whiskey distiller if he wants to be. You help me teach him.”

Nearest was up for the challenge. For so long, Nearest worked alone, but now he had an apprentice. When Jasper turned 14, he was only five feet tall and had a baby face. It hid the struggles he had endured in his life. He was the youngest of 10 siblings. His mother died when he was four months old and he escaped a difficult home life with a stepmother who loathed him. He ran away to work at The Reverend’s farm as a hired hand.

Working with Nearest was a refuge for the boy, and he became obsessed with whiskey making. Jasper studied Nearest’s work and methods. After many years of experimentation, Nearest had developed his own type of whiskey. He perfected a new way to filter the alcohol through charcoal made from sugar maple, and then age it in charred oak barrels. Using this method, his 100 proof whiskey had a unique smokey flavor and an uncommon smoothness.

Two years passed. Together, the runaway teen farmhand and whiskey making slave worked to perfect the recipe. The Reverend and Nearest also taught Jasper about the business side of whiskey making. It wasn’t long before Jasper was taking bottles into town and selling them.

News spread from Huntsville to Nashville about the whiskey coming from The Reverend’s farm. Suddenly, the world changed. The Civil War was raging, and President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. Slavery was abolished, and two years later, the South finally surrendered. Nearest became a free man. He could go anywhere, and he chose to keep working with The Reverend and Jasper.

By this point, The Reverend’s congregation hated the fact that their minister ran an alcohol distillery. The Reverend’s wife gave him an ultimatum: He could either be a preacher or own the distillery, but he couldn’t do both.

Reverend Dan Call sold his whiskey operation to Jasper in 1866, and Jasper’s first decision as a business owner was naming Nearest as his head distiller. Nearest accepted, and many of the men they hired were former slaves. Nearest continued to perfect the recipe he and Jasper had spent years working on.

Meanwhile, Jasper traveled to sell their whiskey all over Lincoln County. Jasper was a serious businessman, but at a glance, he didn’t look like it. At 20 years old, he was five foot one and still had that baby face. To try and hide it, he grew a goatee and a long mustache.

Jasper had spent months trying to find the perfect bottle for their product. Finally, he found a glass design he liked. As he said, “it was a square bottle for a square shooter.” Jasper renamed the distillery after himself and started putting his own name on the now famous square bottles.

15 years passed with Nearest and Jasper working side by side to perfect their famous whiskey recipe.

In 1884, Jasper moved the distillery five miles down the road. He had purchased the land for the Cave Spring Hollow, a deep spring with thousands of gallons of fresh water. This was the final ingredient needed to perfect Nearest’s recipe. Right before the move, Nearest retired at the age of 51. Jasper hired Nearest’s sons, George, Eddie, and Eli to work for him at the new distillery.

Jasper didn’t have children, and over the years, he would take pride when Nearest’s grandsons – Ott, Charlie, and Otis – joined to work for the company, too. In fact, seven generations later, Nearest’s descendants still work in Lynchburg, Tennessee… at that same distillery… the distillery famous for its square bottle… the Jack Daniels distillery.

Jasper Newton Daniel, or as the world knows him, Jack Daniel, didn’t always know how to make his famous whiskey. He was taught by Nathan Nearest Green, who was known to everyone as Uncle Nearest. He was the first African American master distiller on record in America, and he was the first in a long line of master distillers at the Jack Daniels distillery.

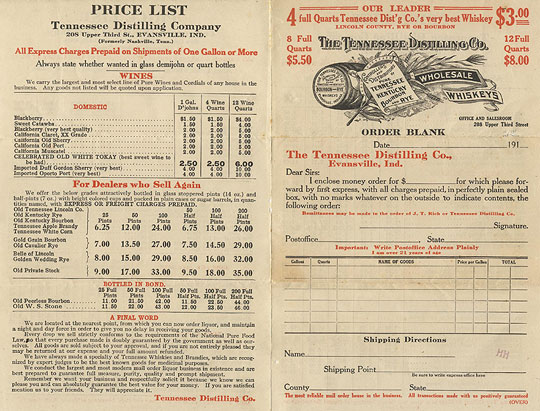

Uncle Nearest’s whiskey filtering innovation was called charcoal mellowing, and in the whiskey making world, his technique is still known and revered today as the Lincoln County process. It’s the process required to make one of the most popular whiskeys in the world, Tennessee whiskey.

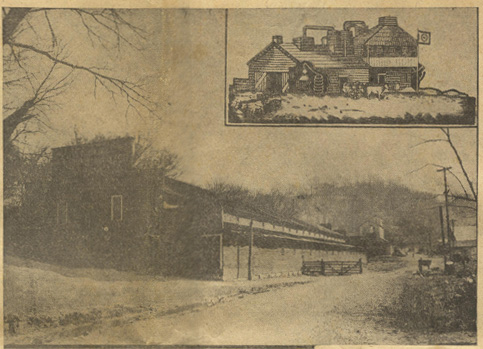

In 1904, Jack Daniel took their smoky, uncommonly smooth, 100 proof whiskey to the world’s fair in St Louis. It won the gold medal, and the rest is history. Today, more than 193 million bottles of Jack Daniels Old Number Seven are sold annually.

Uncle Nearest’s story was almost forgotten. There’s no record, even when he passed away, but thanks to the work of author and entrepreneur Fawn Weaver, Nearest Green’s story is finding new light. Not only is his story living on, so are his whiskey making methods.

Uncle Nearest 1856, a recreation of Nearest’s 100 proof whiskey, is now available at stores and bars nationwide. Nearest Green was born a slave, became a master, created something that has lasted for generations, and died a free man.

If you’re 21 or over, and you choose to drink, make sure you do it responsibly. And if you choose to drink, remember the story of how Uncle Nearest and Jack turned Tennessee spring water into gold.

That’s his story. What’s yours going to be?