Or listen in your favorite podcast app

Apple Podcasts / Google Podcasts / Spotify

—

The Story is brought to you exclusively by Salesforce, a company that is committed to building a path toward Equality For All.

—

One-by-one the chemist examined each piece of material under a microscope.

“Mmhmm… mmhmm,” he mumbled to himself.

He made some notes in his journal.

Sweet Potatoes – failure.

Dandelions – failure.

He listed out dozens of other plants — all failures.

The chemist leaned back from the microscope with a sigh.

He’d been at this for months without any success and was starting to wonder if what he and his business partner were attempting was even possible.

“No…,” he thought to himself. Doubt wouldn’t lead to the discovery they needed.

There were hundreds of plants left to try and thousands of possible chemical combinations. It was a daunting task, but he knew that at least one combination would create the material that they — and the country — needed.

With new resolve, the chemist got up from his desk, went to the back of the lab, and picked out another batch of samples.

Returning to his microscope, he went back to work.

His notebook filled with similar results:

Cattail – Failure

Clover – Failure

Thistle – Failure

Pigweed – Failure

Goldenrod – Fail…

Wait… he stopped writing halfway through.

He peered back through the microscope and squinted, focusing the lens in and out. Sitting back, he rubbed his eyes, unable to believe what he saw. He analyzed the material one last time before going back to his notebook.

Shaking from excitement, he crossed out the half-written word and replaced it with the word “success.”

A grin spread across his face. His persistence had paid off…

70 years earlier, toward the end of the Civil War, the man was born into a slave family in Missouri. When the boy was just an infant, he, his brother, and his mother were kidnapped by a slave trader and held for ransom.

Their owner, Moses, made a rescue attempt. The boys were safely recovered, but unfortunately, their mother was killed at the hands of the traders.

With no family left, Moses adopted the two boys. When the Civil War ended, Moses and his wife continued to raise them.

They were well cared for and Moses taught them how to read and write. The young boy was bright and loved scholarly work.

But he never wanted to focus on studying. Instead, he spent his time working with plants and experiments.

The kitchen and garden overflowed with his tests and concoctions. He experimented with alternative growing methods and natural fertilizers. By age 8, his neighbors referred to him as “The Plant Doctor” — some even asking for farming advice and fertilizer recommendations.

At 11, his adopted parents insisted that he pursue a formal education.

The boy enrolled in a nearby school… but he didn’t last long. From day one, he was dissatisfied with the teachers, the subjects, and the other students. He wanted to spend all of his time in the garden, but schoolwork made that impossible.

He dropped out.

He was still just a boy when he struck out on his own, heading west to Kansas. There, he hopped from job to job and from school to school.

Eventually, he earned his high school diploma and enrolled in college.

The man was still disinterested in his schoolwork, but one of his professors saw that he was exceptionally intelligent. He heard about the man’s amateur work in botany and encouraged him to continue his graduate studies.

The man took the professor’s advice and earned his Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees in Agricultural Science.

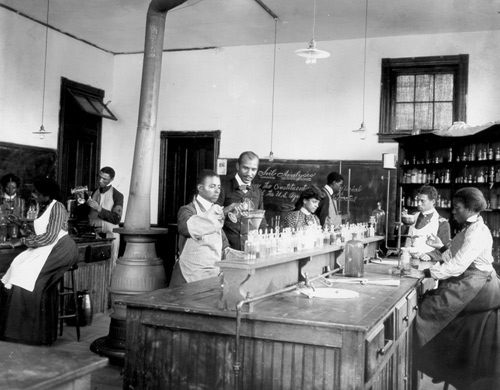

He was offered a position as a teacher and researcher at the Tuskegee Institute, a vocational school for newly freed slaves. In a letter to the man, Booker T. Washington, the institute’s founder, said:

“I cannot offer you money, position or fame. The first two you have. The last from the position you now occupy you will no doubt achieve. These things I now ask you to give up. I offer you in their place: work—hard, hard work, the task of bringing a people from degradation, poverty, and waste to full manhood. Your department exists only on paper and your laboratory will have to be in your head.”

Intrigued by the opportunity, the chemist accepted the offer.

He developed numerous fertilizers and agricultural methods that helped rural farmers get the most from their harvests. He encouraged the farmers to stop planting nutrient-draining crops like cotton and corn, and instead plant nutrient-rich crops like peanuts and sweet potatoes.

He became well known across the country for his revolutionary farming practices and innovative uses of plants, which lead to statewide teaching tours. His methods helped poor southern farmers increase their production.

But crop farmers weren’t the only people interested in his new techniques…

During one of his tours, a businessman from Michigan saw the chemist’s work and was intrigued. The businessman sent the chemist a letter with a proposal. It read:

I have been studying your work for some time now, but it was not until this past month that I saw a real opportunity for how our work could complement one another.

The world will undoubtedly need a substitute for gasoline in the not too distant future and I speculate that a plant-based fuel is the solution.

I am also interested in seeing how alternative crops could be used to make other products — plastics and paints, for example…

The letter went on to explain some of the materials they were already using at his company, and the businessman asked for the chemist’s take on what they could improve or change.

The chemist went back and reread the letter. He wants to run a car on plant oil?! This businessman is either crazy or a visionary. The chemist couldn’t decide which.

Thinking it couldn’t hurt to answer some of his questions, the chemist decided to reply.

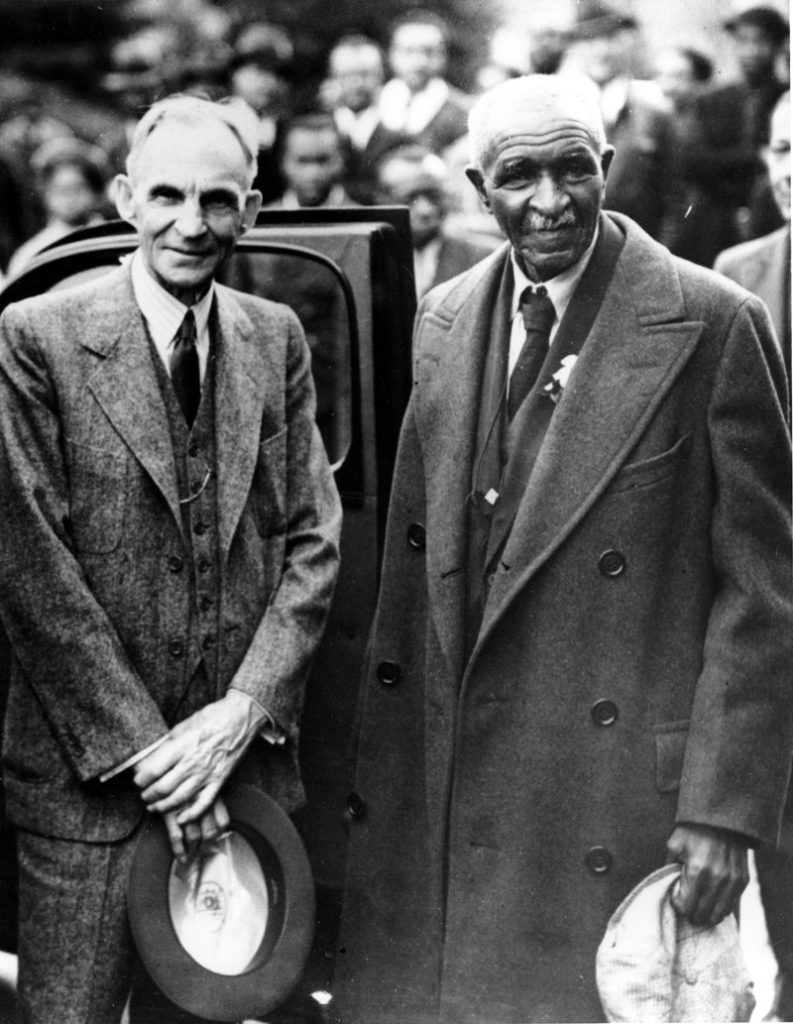

A friendship blossomed, and the partnership would prove to influence the chemist’s work for the rest of his career.

Over the next seven years, the two friends wrote constantly to one another about everything from plants and farming, to car production and education reform. Each would make trips to see the other – the businessman to the Tuskegee Institute and the chemist to the man’s company headquarters in Michigan.

When WWII began, the businessman saw an opportunity for them to work together on a new project. The wartime rubber shortage was hurting his company’s production, and he thought they could solve the problem by making a plant-based synthetic rubber.

The businessman began visiting the chemist more frequently; trying hard to convince him to move his lab to Michigan.

Interested in the project and happy to work more closely with his friend, the chemist gave in. He relocated his lab and research to Michigan. From there he began working on solving a seemingly impossible chemical equation.

Months later, the chemist sat in his lab marveling at that wonderfully beautiful word… “success”.

He grabbed his pen and wrote another letter to his quirky business partner…

To the greatest of all my inspiring friends,

How fitting that the breakthrough should come while you are out of town on business…

We have successfully created a synthetic rubber.

You would never guess which plant ended up working… Goldenrod.

Travel safe and come home soon. I can not wait to show you and Mrs. Ford what we have discovered.

Your ideas are revolutionary and I see even more big innovations just ahead of us.

With love and best wishes, I am most sincerely and gratefully yours,

George Washington Carver

Carver folded the letter, put it in the envelope, and addressed it to “Mr. Henry Ford.”

Throughout his time working with Carver, Henry Ford donated considerable amounts of money to the Tuskegee Institute to help fund Carver’s work. Even after their deaths, Ford Motors has continued to donate millions of dollars to the university.

When the United States was dealing with a massive rubber shortage during World War II, it was Ford’s donations, encouragement, and (sometimes outrageous) ideas that helped Carver discover the exact chemical formula needed to make synthetic rubber.

Carver’s research into agricultural science reformed the way farmers in the deep south grew and harvested crops. His methods helped dramatically increase the standard of living for farmers and agricultural communities throughout the country. Together, two friends, George and Henry, forged a partnership that helped get the U.S. through the war.

George was buried next to Booker T. Washington on the Tuskegee grounds. His epitaph reads:

“He could have added fortune to fame, but caring for neither, he found happiness and honor in being helpful to the world.”

That’s his story. What’s yours going to be?